In his shrill response to Max Blumenthal’s letter to the Nation, Eric Alterman continues to question Blumenthal’s claim that the Israeli thinker Yeshayahu Leibowitz was revered by the Israeli left. He takes issue with what I wrote in the post below, which Blumenthal had quoted.

I have no desire to respond to Alterman’s defense of his claim that “Jews all over the world ‘revered’ Leibowitz for the brilliance of his Talmud exegesis” except to reiterate the accepted scholarly (and obvious) view that Leibowitz’s writings on Jewish philosophy do not constitute Talmudic exegesis. Obviously as a philosopher writing about Judaism, Leibowitz occasionally cites and creatively interprets the Talmud, as does Martin Buber and Michael Waltzer. But this doesn’t make him, or them, brilliant Talmudic exegetes.

As for being revered by “Jews all over the world,” I wish Leibowitz were better known outside of Israel. I have been teaching his thought for over thirty years, and I attended his public lectures in Jerusalem. Enter any synagogue in the US (including orthodox) and ask Jews if they have heard of Yeshayahu Leibowitz, and you will generally encounter blank stares. The philosopher’s sister Nehamah is much better known, especially among the orthodox. And pace Alterman, how many Jew outside of Israel are familiar with Ha-Entziklopedia ha-Ivrit (the Hebrew Encyclopedia, which he may be confusing with the Encyclopedia Judaica) of which Leibowitz was once editor-in-chief?

In any event, I claimed that Alterman was confused about Leibowitz. It turns out that the Leibowitz with which Alterman is acquainted is the Jewish philosopher whom he studied in a New York yeshiva and whose philosophy merited an entry in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Full disclosure: I am one of SEP's editors on Jewish philosophy.) That apparently explains his surprise at Blumenthal’s claim that Leibowitz was revered by the Israeli left.

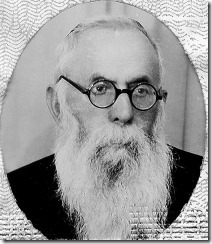

But the Leibowitz known and revered by the Israeli left was the outspoken moral critic who foresaw already in 1969 how the Occupation would cause Israeli society to rot, who accordingly demanded an immediate total Israeli withdrawal to the 1949 armistice lines without a peace agreement, who referred to the nationalist fervor around the conquest of Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza, as “fascism,” who coined the memorable term “Diskotel” for the religio-nationalist infatuation with the Western Wall (‘Kotel,’ in Hebrew), who called the religious Zionist settlers “worshippers of stones and trees” (i.e., idolaters), and who claimed that the Israeli public enjoyed the murder of Arabs in Beirut in 1982, predicting that Ariel Sharon and others would establish concentration camps for him and his ilk. (Much of the above can be found in Leibowitz's book advertised here and on a Hebrew website here; for a good English website devoted to his multifaceted career see here.)

Alterman correctly remarks that Leibowitz was not awarded the Israel Prize because of his “Judaeo-Nazi” statement, but he neglects to point out that he did not attend the ceremony because of the public outcry over the award. But again, Blumenthal’s point was about Leibowitz’s fame among the Israeli left, not the Israeli public at large, or scholars of Jewish thought.

Was Leibowitz indeed revered by the Israeli left? On the centennary of Leibowitz’s birth in 2003, and at the height of the Second Intifada, the Haaretz magazine section published a cover article whose inside headline began, “What remains of the worship of Yeshayahu Leibowitz?” That “worship” was not of the Leibowitz the philosopher but of the sharp-tongued social critic who railed against the establishment. The fact that the Left did not understand that critique in context of Leibowitz’s religious philosophy is irrelevant to that reverence.

Is Leibowitz now revered by the Left? Two months ago Haaretz’s intrepid columnist and critic Gideon Levy delivered a birthday tribute to that grand Israeli leftist, Ury Avnery, saying, “Avnery was one of the first to utter the words that everyone mumbles now – ‘two states for two peoples.’ Together with Yeshayahu Leibowitz and the radical socialist organization Matzpen he was the pillar of fire that went before the camp.”

From Leibowitz and Matzpen to Avnery and Levy there is an Israeli tradition of harsh criticism of mainstream Zionist policies towards the Palestinians. Leibowitz’s moral criticism against the actions of the Israeli army and its government began already in the early fifties. This earned him the reverence of the left.

Perhaps I did Alterman an injustice for inferring that he did not know the above. He gave his readers no reason to believe that he did.